|

A CENTENNIAL CELEBRATION! |

|

|

THE QUENTIN CRISP ARCHIVES

ROBERT PATRICK

Friend and playwright

|

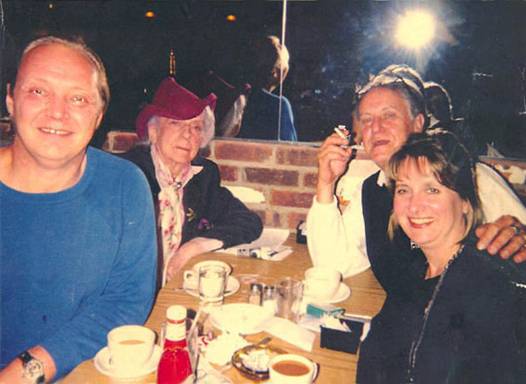

Having seen Quentin Crisp in a movie during a Manhattan TV station’s British season, I recognized him across Second Avenue at Fifth Street in front of a restaurant universally called “The Greek’s,” standing in the middle of a circle of policemen. Gingerly, I crossed the avenue and asked, “Mister Crisp, might I be of some assistance?” He smiled with a puzzled expression, then brightened and exclaimed, “Oh, you probably mean these gentlemen here! Oh, no, there is no problem. This is America. They simply want my autograph.” I took him to lunch at the Greek’s, and we became friends. I had dreamed of conversations with witty, gallant spirits like Noel Coward or Dorothy Parker. With Quentin, the dream was realized. Any ordinary utterance, such as ordering food in the restaurants where nearly all our meetings took place, was delicately turned in a manner I recognized as Victorian politeness combined with 1930s American movie sassiness. He would hold forth when it was clear that that was what his tablemates desired, or become the most sympathetic, articulate, and understanding listener. He delighted in playing roles, and instantly picked up on any conversational cue to assume one, as when I’d play his concerned, fussy parent or beseech him as an almighty authority to pass judgment on a film or play. Most of all, he liked to recount something that had just happened to him, an encounter or interview, often tedious and tiresome, rendering it, by deft phrasing, amusing and delightful, like a verbal caricaturist, an oral cartoonist. He would treat a full table at The Greek’s or Phebe’s as an audience if that was what they wished to be, or he would simply relax and chat like any mortal man (only better) with people who simply liked him and enjoyed his company. Such people were I and my acting troupe, The Fourth E Company. We did plays at a verminous ruin on the same block as Phebe’s, so all but lived in that famous watering-place when not actually rehearsing or performing—or working day-jobs. Quentin, who joined us at a window-side table if he found us there, or beckoned us to his if we came later than he, was amazed at the quality of our work, astonished that we were not paid for it, and in the end, I think, awed by a corner of New York not intimately involved with money. I also ran into Quentin now and then on what he called the “wet napkin” circuit, named for the soppy token always moistening one’s hand under a plastic glass of white wine at a reception, exhibition, gallery, or mere blatant photo op. A magnet for the celebrity-mad, and himself an important analyst of the phenomenon of star-worship, Quentin was in life indifferent in person to the prestige or lack thereof of others, and chatted with the most gushing fan as easily and respectfully as he did with Tennessee Williams or Liza Minnelli. I arranged for him to meet a very young gay writer and a very old gay painter. As it happened they were both conservatives, put off by Quentin’s dandyism. He was delighted to have met them and unfazed by their disdain. I was seldom alone with Quentin in his cozy, dusty little lair on East Second Street, and then only when he needed something carried up the stairs or taken to a repair shop, or when he was ill. I tended him so assiduously during one cold that he seemed to think I had ulterior motives, and very cautiously explained to me that he very seldom felt the need for sexual expression anymore. I think my laughter relaxed him. The incident reminded me that no matter how much love and care and respect he now had lavished on him, he was still the product of over half a century of fantastic mistreatment and manipulation. Adored and in demand as he was in his chosen city, he was quite the happiest man I ever met. I was therefore somewhat put off to see how in Resident Alien, Mister Jonathan Nossiter’s documentary of Quentin’s life in the Big Apple, editing and commentary made Quentin seem sad and desperate. But Quentin didn’t mind, and so I shrugged it off. Quentin made that movie, as he did everything else, “because I was asked to.” Invitations to parties or invitations to work were all one to him—recurrent proofs that he was out in the world at last. Therefore he was often “taken advantage of,” a term he greeted with raised brows and averted eyes when friends used it of some project he had been involved in. He felt that nearly anything was better than the frightened solitude of his earlier years. I fancied that invitations to my plays were welcome pleasures to him, but perhaps he simply had the magic gift of making every person feel special. In Phoenix, I gained my favorite image of the dear man. In a nightclub, young people who had come to sit at tables and gawk at the TV celebrity telling funny stories, stayed long after the show, on the stage at his feet, asking him the most basic questions of young people facing life without guidance. So must Socrates have looked. The only time I ever heard Quentin complain was in the last month of his life when he called me from England, where he was appearing in his one-man show. He said he hadn’t meant to go to England ever again, but, “I was asked.” Word of his death was circulated worldwide shortly thereafter. Here with a poem he sent for my birthday in 1995. I retain his punctuation and capitalization.

|

|||

Site Copyright © 1999–2009 by the Quentin Crisp Archives.

All rights reserved.