SUFFERING A FOOL GLADLY by Frank Mitchell |

|

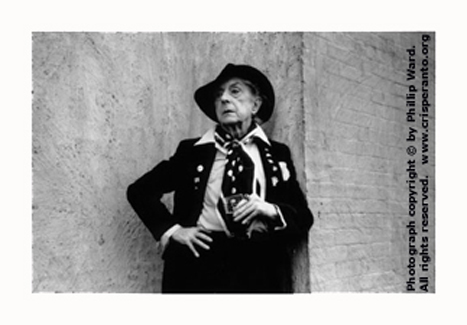

When I first heard that the great Quentin Crisp had actually died (and in England!), I went into a complete state of shock. I was in the Street Roots newsroom, Portland Oregon's newspaper for the homeless, where I did volunteer work teaching a creative writing class once a week. I was sitting at my desk, probably trying to read a sonnet or ballad one of my homeless students had written, when the phone rang. I answered it at once. "Well, are you sitting down?" (Why do people always say that when they are about to tell you someone has died?) It was my close friend Roy. I actually thought he was about to tell me that John, his roommate and another dear friend of mine, had died suddenly. "Did something happen to John?" I asked, after my racing heart had calmed down a bit, and I could actually string a few words together to form a complete sentence. There was a long, long pause. "No, John is okay," he answered. "But Quentin Crisp died today in England. I just heard the announcement on the radio half an hour ago." I could not speak. I just remember staring at the clutter on my desk, and thinking this is all a very big mistake. I'd lost all sorts of people close to me during that terrible decade of death: My sister. My brother. My mother. My grandmother. My step father. My lover. And I was very saddened each time I received the terrible news. Very, very saddened. But this was something else entirely. I was literally speechless. "Are you okay?" my friend asked me three times before I managed to finally reply. "No, I'm really not," I said. And something warm and wet trickled down my cheek and landed on one of the poems I'd been reading before the terrible call. I didn't even bother to blot it up. "I better go now," I said, and hung up the phone without saying another word. Then I grabbed my jacket and backpack, and walked out of the office, not even certain where I was going. Ours was a very curious friendship. For I am certain he considered me a fool at best. A bore and a bit of a pest. Someone to suffer gladly. I can only say these words to you now because I am finally healthy again. Seven years without a drop of booze! Yes, I can see quite clearly now the drunken fool I was when I used to call him up at 1 a.m. his time, all the way from Chicago, and shamelessly beg for a little bit of his wit and wisdom to see me through another miserable night. My sister had just died suddenly in a car wreck. My lover was recently diagnosed with full blown AIDS. And I was certain I was HIV positive myself, but was too afraid to take the test. And I couldn't write anymore! Not even a poem. I was all washed up at the insanely young age of 28. Blah, blah, blah. He was always so very polite to me, and even concerned. I remember he suggested I take the test. That I had nothing to lose. It would be better to know for certain. And to not worry so much about not being able to write. For there were already too many books in the world. And that we were all going to die one day. And how he wouldn't wish immortal life on his worst enemy. He always made me smile. Even if I had read or heard him say these wise and witty words many times before. "But not you, Mr. Crisp," I said, in a mock serious voice. I rattled the ice cubes in my half full glass, and stared at the bright pulpy liquid within. Orange juice and vodka. "Oh yeeeees," he said at last, "I will die too. And I am looking forward to it. So dry your tears." I let out a long self-pitying sigh, and asked him what all the lonely people in the world would do without him? I mean, who else could we call at 1 a.m. and chat about our fears and disappointments with? A brief pause then. Just long enough for me to take a quick gulp of my very stiff drink. "You are very kind," he said, in an exhausted voice. Then a long awkward pause. "Well, it's after 1 a.m. your time," I said. "So I'd better let you get some rest now, huh?" A brief pause. "If you like," he answered. Always the polite gentleman. Even while being subjected to a drunken fool at 1 a.m. That would have been in 1990. The first time I wrote him a two-page fan letter, outlandishly praising The Naked Civil Servant and The Wit and Wisdom of Quentin Crisp as two of the wisest and wittiest books I'd ever read. As good as Shaw! And better than Wilde! He sent me a polite reply within a week! And he included his home phone number! I was in a state of bliss. I actually was foolish enough to believe he had singled me out. So I began to ring him up, always very late at night. With a tall drink nearby. When I couldn't sleep, and there was nobody else to talk to. I must have bothered him at least ten times during that long alcoholic summer. And he was always quite friendly. And he really did seem like my friend. There was great comfort in knowing I could always call him, no matter the hour, and tell him everything, as he was so fond of saying. Until one dark day, after I had sent him perhaps one too many self-pitying letters and/or cards. And I had dialed his number after 1 a.m. one too many times, and he had suffered me gladly and with enormous patience, he finally let me know, in that oh so polite and generous way of his, that I had perhaps finally worn out my welcome. "Am I bothering you too much, Mr. Crisp?" I asked. "Just say the word, and I promise not to call you again." A longer pause than usual. I gulped down half my drink because as stupid and selfish as I had been, I knew there was only one answer I truly deserved. And it made me very sad to think I had only managed to alienate him in the end, a man I truly admired perhaps more than any other I'd ever known. "If you like," he said at last. And I suddenly felt very ashamed. My face turned bright red. I finally understood that I'd been acting like a silly little fool, taking advantage of this kind old man's generous heart. "I am sorry, so very, very sorry," I blurted out. "I promise I won't bother you again. Goodbye Mr. Crisp." A long pause. "Goodbye," he said at last. Well, I did manage to leave him alone for awhile after that last devastating phone call. But I always felt I owed him some sort of an explanation for my insane behavior, and I really did miss him, so after I had managed to give up the booze for an entire year, I wrote him a short letter, and he sent me back a very polite reply. I'd mentioned that I was writing again, and even getting a few of my poems published, and he wrote that he was happy for me. He also added that being a poet was a terrible thing! And I laughed and laughed at the wisdom in his remark. And so it went. Once a year, I would send Mr. Crisp a long letter telling him about all the wonderful things going on in my life. And he always sent me back a wise and witty reply. In 1995, he wrote me that his health was beginning to fail him, and I started to worry he might die before he received my next letter. So I swallowed my pride, and started calling him again, once every 6 months or so, to ask about his health. But it was very different now. For I was doing most of the listening for a change! And he would tell me about all these mysterious things happening to his body, and how there was no logical explanation for it, and I would comfort him as best I could, and suggest he find a good doctor, and he would always answer that doctors expected to be paid! I knew this was just more of his wit, but it was not always easy to laugh at his humor when I sensed that Mr. Crisp was not a very well man at all anymore. He would have been 86 years old by this time. I always felt a terrible sadness after I hung up the phone. He just sounded so terribly exhausted. I knew it could be the last time. And that was too painful to even imagine. In the fall of 1997, I moved to Portland, Oregon. I thought it would be a good place to write. So close to the ocean. Tall mountains. Lots and lots of talented poets. The City of Roses. In November, Mr. Crisp was scheduled to perform his one man show here, and I could not believe my luck. I was finally going to meet my long distance friend! I walked to the Scottish Rite Temple, about a mile and a half from where I lived, and sitting in the balcony, I listened to him utter those famous witticisms of his that I'd known and loved for so many years. He gave a very strong performance, and received a long standing ovation at the end. I stood up and clapped as long and loud as I could. Then there was an announcement that Mr. Crisp would be signing copies of his books downstairs, and I was so happy I'd decided to bring my paperback copy of The Naked Civil Servant along with me. Also, I had several crossword puzzles that I'd carefully clipped out of The Oregonian and saved especially for him. Because I knew how very fond he was of them. So I stood in line with a bunch of other gay men and women, pretending to read my paperback copy of The Naked Civil Se  rvant, as I inched closer and closer to him. I didn't know what I would say to him when it was finally my turn. I mean, apart from my name, he had no idea who I was or even what I looked like. rvant, as I inched closer and closer to him. I didn't know what I would say to him when it was finally my turn. I mean, apart from my name, he had no idea who I was or even what I looked like.He was wearing a handsome black suit, with a jaunty black cowboy hat. And a bright purple scarf around his neck. And a huge dark ring on his finger. But he still looked very tired and weak to me. A very brave and sweet old man trying to sign too many copies of his own books. So after he signed mine, and I'd given him the crossword puzzles, before I lost my nerve, I asked him if I could please shake his hand. He sized me up with those great intelligent eyes of his for a moment, and I wondered if I had once again perhaps asked him for too much. I almost told him who I was then, just so he would know that I wasn't a total stranger. That I was his long distance friend from Chicago. The fool he had been suffering gladly for more than seven years. But his hesitation made me even more nervous than I already was, and there were still many, many fans waiting to meet him. Suddenly I reached for his frail hand, and thanked him for loving the unlovable. He smiled warmly at me, then I smiled back. And I didn't feel like such a fool anymore. Copyright © 2005 by Franklin Mitchell. All rights reserved. Used by permission. Photograph copyright © by Phillip Ward. All rights reserved. |