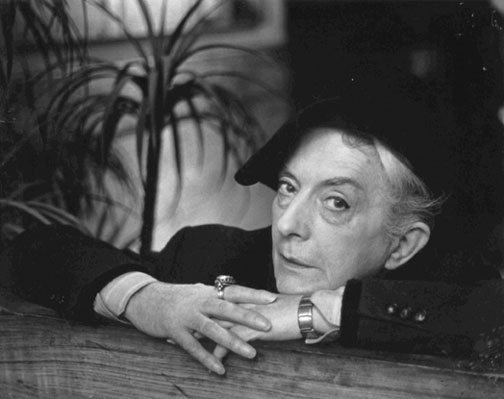

Though a supremely gifted writer, Quentin Crisp has achieved a good deal of his fame simply by being Quentin Crisp. Born in England in 1908, Crisp's flamboyant appearance and mannerisms revealed his homosexuality at a time when being gay was a dangerous thing. His first memoir, The Naked Civil Servant (1968), has been turned into a play and a movie (starring John Hurt), and was recently reissued as part of Penguin's Twentieth-Century Classics series. In the '70s, Crisp took up residence in New York, his experiences inspiring Sting's 1987 song "Englishman In New York." While continuing to write, Crisp has made numerous lecture appearances, appeared in projects as far afield as the films Orlando (1992) and To Wong Foo, Thanks For Everything, Julie Newmar (1995) and ads for Calvin Klein perfume and Levi's jeans. His latest book is this year's Resident Alien: The New York Diaries. Crisp recently spoke to The Onion about England versus America, acting in the movies, and the importance of being courteous.

Keith Phipps: More people probably know your name or face than know who you are or anything about your life, so maybe you could give us a short history of it.

Quentin Crisp: Well, I lived in England all my life until I was 72, and then at last I had enough money to pay to leave it, so I came to America. I've always been American in my heart, ever since my mother took me to the movies.

KP: Why is that? What's the difference between being American in your heart and being English in your heart?

QC: Well, being English in your heart . . . England is very dreary, but I'm a people person. I would never go to a place and live there because the weather was good or the scenery was beautiful or the architecture was wonderful. I would only go because the people are kind, and in America, everybody's your friend and happiness rains down from the sky. And in England, nobody's your friend. So, I at last could leave, and I came to America, and someone said the other day, "You came to America when most people decide to go into a nursing home." Which is true; I was already 72, but I couldn't pay my fare before that. I came first to America in 1977 at the invitation of a man who wanted to make my life story into a musical. But my agent said it was not to be and it was never done. So I went back, but I'd seen New York, and I wanted to live there. Because everybody talks to you in the street. See, nobody talks to you in England.

KP: Right. I lived there for a year.

QC: Oh, well, you know what it's like. A vast, rain-swept alcatraz. So I came here then, and I lived in unaccustomed splendor on 39th Street until one of my spies found this room, by knowing someone who knew someone who knew the landlord. I've always lived in the same way. I lived in England in one room in a rooming house, and I live here in one room in a rooming house.

KP: Why is that?

QC: Well, because I've never found out what people do with the room they're not in. So I stay in one room, and it's easier to live there, to control it, to make it warm. It seems to me a convenient way to live, and it's cheap. Of course, England was much cheaper than America. But still I can manage. I've never worked since I've been here, that's another thing. You see, I have to work in England, but here you don't have to work. You can sort of enter the profession of being.

KP: So you never miss England?

QC: Oh, I never miss England. No, someone said to me, "Don't you miss anything about England?" And I thought, "My gas fire." Here, there's no method of heating your room. Your room is only as warm as the super decides it should be. Today, for instance, I'm shuddering in my room because there's no heat. When I got here, I was writing a book, Manners From Heaven (1984). Then I . . . I sort of went . . . I don't know how to describe it. I talk to the multitude wherever I am, and that provides a living. I only tell them how to be happy, because happiness is the only thing I understand.

KP: What do you usually tell them?

QC: Well, I tell them not to do any of the things their mothers tell them—not to clean the place where you live, and not to wash the dishes, and all that. It's all a waste of time. I never spend my time doing anything I'll have to do again tomorrow. And I went recently to Los Angeles and told them how to be happy. Then I went to San Diego, which is wonderful, although California on the whole is a weird place—it's always burning, or flooding, or shaking, or something. San Diego is always a cool summer, and I went there and told them how to be happy, and then I came back here. I go wherever my fare is paid. It's a strange situation, but people will pay your fare to get you to go and tell them how to be happy.

KP: Well, probably not most people. You're probably one of the few people whom people will pay to have you do that.

QC: I don't know why.

KP: Well, it's possibly because you've made a lifetime commitment to disregarding what people expect you to do and what conventional morality would say you have to do.

QC: That's right, yes. You don't have to do anything. I don't believe in convention at all. I do what I have to do to stay alive.

KP: Was there a moment when you decided that there was no point in trying to fit in? Was there a moment when you realized that you had to wear your identity on the outside, that you couldn't be a closeted gay man?

QC: People say to me, "When did you come out?" But I was never in! When I was about six, I was swanning around the house in clothes that belonged to my mother and my grandmother which I'd found in an attic, saying, "I am a beautiful princess!" What my parents thought of this, I don't know. But they bore it. And the real problem was not my sin, but my unemployability. So I went out into the world when I was about 22. I wrote books and I illustrated books and did book covers, and I taught tap-dancing, and I was a model in the art school. I had no ability for any of those things, but what else could I do? You see, it may be true that artists adopt a flamboyant appearance, but it's also true that people who look funny get stuck with the arts. And that's what happened to me. And then I came here, and I'd written several books before I got here—The Naked Civil Servant and so on. When I got here, I just went on doing the same things. I wrote books. I haven't illustrated anything here, because now I'm too old to make drawings. I don't see well enough, and my hand isn't steady enough. But that's how I came here.

KP: Would you say you're happy now?

QC: And now I'm happy. I don't ever have to pay anything, and I don't ever have to wash the dishes, and I don't ever have to behave nicely. You can behave as badly as you like in America. Nobody notices.

KP: Would you say you owe it all to the change in location? Because The Naked Civil Servant ends with such a tragic turn of phrase. ["Even a monotonously undeviating path of self-examination does not necessarily lead to a mountain of self-knowledge. I stumble toward my grave confused and hurt and hungry..."]

QC: Yes, it has. Yes, it has made a wonderful difference.

KP: Do you think the change in political climate allowing more freedom for gay people has had something to do with it as well?

QC: That's true, there is more freedom. You see, America believes in freedom. The English don't believe in it. They don't believe in happiness.

KP: And you think Americans generally do?

QC: Yes, it's written into the Constitution that you're allowed to pursue happiness. In England it would be considered a frivolous objective.

KP: Do you still do movie reviews?

QC: No, I can't do movie reviews, because the paper has folded. I worked for Christopher Street [a New York-based gay newspaper]. I worked for The New York Native writing my diary. And now that kinkiness is mainstream, you don't have to buy papers like that to read the shocking things. You can read them in The Wall Street Journal or the Sunday Times.

KP: What's an average day like for you? What do you do on a day-to-day basis?

QC: Well, I do two things. On a day like today, I don't go out at all, and then I can remain wrapped in a filthy dressing gown, doing absolutely nothing. And someone said, "I don't think you should say that. Couldn't you say you meditate?" So I meditate.

KP: On a busy day, what do you do?

QC: Well, I wake. I reconstruct myself, which takes about two and a half hours, and then I go out. You see, if you don't stay in some days, you can't recharge your batteries. In Manhattan, when you're out of the front door, you're on, and you have to be ready to smile and speak to people. Everybody who's been on television more than once wears in public an expression of fatuous affability. Because you may be addressed at any moment by somebody.

KP: Do you get approached a lot?

QC: More than most people. Not a lot, but every day someone notices me and waves to me, or stops and speaks to me, or asks me for an autograph, or photographs me.

KP: Do you mind that?

QC: I don't mind it. I don't know why people are so angry about it. I reviewed Mr. [Alec] Guinness' diary, which was a little book about 18 months of his life, and all he did was come up from his country home to London and eat expensive meals and go back again. And the only thing that ever annoyed him was being recognized. Well, he wasn't recognized by teenagers trying to tear off his clothes! He was recognized by middle-aged ladies saying, "Surely you're Mr. Guinness?" And all he had to say was, "Well, how charming of you to recognize me." I mean, it's not trouble. I don't understand why they're cross.

KP: You've seen more of the country than just New York. What do you think of the rest of America?

QC: Oh, yes, all America is much the same. I've been as far west as Seattle, and as far north as Detroit. When you're in Detroit, you eat in a restaurant which turns while you eat. And I've been as far south as Key West, from which you can go no further south. So I've really been all over America.

KP: I recently saw a documentary about you where they had some gay-rights activists who criticized you as being a sort of stereotype. How do you respond to that?

QC: Well, I am a stereotype. I am an effeminate man. And when I was young, I and the whole world thought that all homosexuals were effeminate. And of course they're not. You can just see which people are effeminate; that's the only difference. So, I became a prototype of the effeminate man, because I was conspicuously effeminate. But camp is not something I do, it's something I am.

KP: The other thing they criticized, and this probably comes with camp, was your tragic demeanor. But you don't really seem to have a tragic demeanor anymore.

QC: I don't think I have a tragic demeanor. I can't remember ever having a tragic demeanor. Although my life was tragedy. I was beaten up wherever I went, and people shouted at me and cursed me and threw things at me...

KP: And those are things most people don't have to deal with.

QC: You don't have to deal with anyone in America. They accept you the way you are. I was on a bus going up Third Avenue, and a huge great man sat next to me and said, "Do you live here permanently?" And I said, "Yes." And he said, "It's the place to be if you're of a different stripe." I mean, it is.

KP: And some of the people who criticize you haven't had to deal with those problems; haven't had to deal with being beaten up on the street as you were.

QC: No.

KP: But there were bright spots to your time in England as well, right?

QC: Well, the war was wonderful, of course. I wrote about that. You see, you were in danger, which is lovely, because you look your last on all things lovely every hour. And that's nice.

KP: You recently popped up in a Levi's commercial.

QC: Yes, I don't know how I did that. I didn't put on Levi's. I've never worn Levi's.

KP: I can't imagine you in jeans.

QC: I sat at a table, and you couldn't see my legs at all. And the man said to me, "What do you think?" And I believe he meant of the music, and I only said two words in the commercial. And then when I was in Mr. Klein's advertisement, I went all the way to Brooklyn and went into a huge place where I thought we could film The Charge Of The Light Brigade; it was like an aeroplane hangar. And I found a square of paper and six very thin people standing on it. And a man naked to the waist crawled on the floor between our feet. And I said to Mr. Klein, "What does it all mean?" And Mr. Klein said, "Say that again." So by mistake I'd written the copy.

KP: Did they pay you for writing the copy?

QC: [Laughs.] Yes.

KP: And you've been in movies.

QC: I've been in two real movies. I've been in The Bride (1985). Mr. Sting played Frankenstein and Miss [Jennifer] Beals played the creature that he constructs for the monster. And then I was in Naked In New York (1993), and that was with Miss [Kathleen] Turner and the Karate Kid [Ralph Macchio], and Mr. [Tony] Curtis.

KP: You were also in Orlando. You were terrific in that.

QC: I don't really act. I say the words the way I would say them if I meant them. But I don't know how people act. I've never understood that. I asked a girl who came from America to England, when I was only English, and she admitted she had been to a drama school. And I said, "What did they teach you?" And she said, "They taught me to be a candle burning in an empty room." I'm happy to say she was laughing while she said it, but she meant it. I've never learned to be a candle burning in an empty room. So I go on the screen, and I say whatever I'm told to say.

KP: You played Queen Elizabeth in Orlando.

QC: That's right. It was hell to do. I wore a bonnet so tight it blistered my stomach. I wore two rolls of fabric tied around my waist with tape, and then a hoop skirt tied around my waist with tape, and then a quilted petticoat, and then a real petticoat, and then a dress. And I could never leave the trailer in which they were put on me without someone lifting up the whole lot and saying, "Put your foot down. Forward. More. Now the other one. That's right, now you're on level ground." I could never see my feet during the whole production.

KP: And you were in To Wong Foo, right?

QC: Yes, I was in To Wong Foo. That was very strange. Because nearly always when actors are approached by the beauticians, they try to avoid the dabs that the beauticians put on their faces. They dodge them. But in To Wong Foo, when there was a pause in the filming, everyone was like a bird in a cage. "Me! Me! Look, isn't there something . . . Couldn't you put a bit of powder up there? Is my eyelash slipping?" And so on. They all wanted to be made up.

KP: What I always thought was funny about that movie was that when it came out, all the actors who appeared on talk shows went to great lengths to demonstrate how masculine they were in real life. Did you notice that?

QC: Yes, I never understand that. As soon as a person takes a part as a homosexual, the press says, "What do your wife and children think of this?" And the actor never says, "Well, last week I was a murderer, and the week before that I was a child molester, and the week before that I was a lunatic. But now I'm a homosexual." [Laughs.] He has to lump it all. They all say, "Oh, they're behind me all the way. They approve of it." And I don't know, but it seems very strange. They all object to someone playing a homosexual.

KP: What do you think about the portrayal of gay people in movies today?

QC: Well, I think it's much easier. You see, you don't have to be camp—you don't have to flap your hands and roll your eyes—because nobody does it anymore. See, the world was very feminine when I was young. And now it's very masculine. Because women have decided to be people, which is a great mistake. Women were nicer than people. When I wrote Manners From Heaven, I was interviewed by a woman who asked if I researched the subject. And I said, "Yes, I read all the books I could find about manners, and the extraordinary thing was, in all books up to the end of the Second World War, most were directed at how to comport yourself in the presence of the ladies. And I said, "And now there are no ladies." And she said, "I don't think we're putting up with that, are we, girls?" And the girls said no, and I said, "Well, I thought you decided to be people." And they said, "We are people." And I said, "But you can't be a person and a lady. If you're a person, you can open the damned door yourself." What matters is not whether you put your fork or knife together because you've finished your meal, or something like that. What matters is that you don't offend people, or hurt their feelings by mistake by saying the wrong thing or doing the wrong thing.

KP: A lot of people think New York is a rude city.

KP: A lot of people think New York is a rude city.

QC: No, I think they're wonderful. People have all said that, but I find people so courteous and so generous. Free drinks in bars. Free taxi rides.

KP: Well, a lot of it has to do with the fact that you're famous, too.

QC: Well, I don't know, I've never not been famous. [Laughs.]

This article first appeared in The Onion, October 29, 1997 Volume 32 Issue 13. A print version is available in The Onion's AV Club's Tenacity of a Cockroach. Copyright © 1997 / 2005 by Onion Inc. All rights reserved. Used by permission.