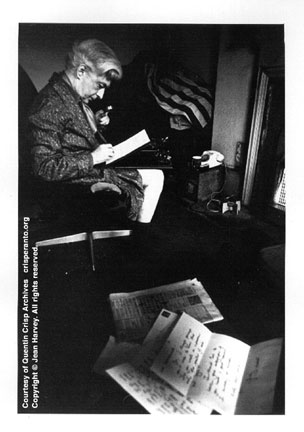

Quentin Crisp was born on Christmas day, 1908. He first became well-known in his fifties, when his autobiography, The Naked Civil Servant, was published. While actor John Hurt turned in an award-winning performance in a British television movie based on that book, Crisp himself has been turning up in movies for several years now, with roles in films like The Bride, Orlando, and the forthcoming Homo Heights, which recently completed shooting in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul. To encapsulate the life of Crisp in one introductory paragraph and interview is virtually impossible, but I caught up with him in late August 1996 to talk about movies and his role as both a spectator of and participant in them.

Chris Lee: What can you tell me about Homo Heights and your character?

Quentin Crisp: I have no idea what the film's about, I have no idea what I'm meant to do or say, but I presume it's one long, gay romp and that I'm part of it. Mr. [Stephen] Sorrentino, who is the star, is in drag with a wig up to here [Crisp motions upwards] and I think I'm his little friend, as far as I know. But I shall do whatever I'm told to do and say whatever I'm told to say.

CL:

So you haven't started memorizing your lines or reading the script?

QC:

I try not to memorize lines because it's so very difficult, and when you memorize them you have to say them and it all gets rather dead if you're saying lines you think are in the back of your head. But I shall learn them if I must and we shall go on from there.

CL:

I've heard you're about to appear in several other films.

QC:

Shoestring movies, as I call them. They are made in the Lower East Side of Manhattan in dim cellars where anything goes.

CL:

Mr. Crisp, which decade did you like the most?

QC:

Decades just glide into one another, gradually getting worse. I don't notice any difference other than that. The world gets louder, faster, sexier.

CL:

Would you say that's a mistake?

QC:

I think it's a mistake, yes. I liked it when it was quiet. And slow. And sexless.

CL:

What would you do when it was quiet and slow and sexless?

QC:

You had more time to breathe and to think about what you would do, and you weren't rushed into situations because everyone wasn't in such a hurry. And you could hear what people said because the music wasn't so loud. I never heard my parents say, "If we're going out for a meal, let's find a quiet restaurant." Now you do it all the time.

CL:

I hear that you go out every night in the East Village, is that correct?

QC:

Oh no, I don't go out every night. I try to spend at least one day—if possible two days a week—without leaving my room, because if I don't, where would I recharge my batteries? Because when you live in Manhattan, it's quite different from living anywhere else. You belong to the city. And when you go out you're in the smiling and nodding racket from the word go, when you leave the house. So, it's very nice but it's very tiring, so there has to be a day, at least, when I sit in my room in a filthy dressing gown, looking terrible, and being my horrible self because otherwise I wouldn't be able to get through it all.

CL:

But you do accept many invitations to lunch and dinner....

QC:

I try to do whatever is offered me because if I, who am only English, am allowed to live in America, what do I give in return? And I'm not able to endow a University or build a wing for a hospital, so I can only give my infinite availability, so I try not to say "No, I won't do things." Occasionally I say, "I am not worthy," which means no, but not often. That's why my number is in the telephone book in Manhattan, so that people can phone me up—and in America that's regarded as extraordinary. I don't know why, everyone in England has his number in the book. I looked up the Westminster libraries when I was in London and above the Westminster libraries I saw "Westminster, Catherine, Duchess of." And if the Duchess of Westminster can have her number in the book, so can I!

CL:

What was the last movie you saw?

QC: The last movie I saw was A Time To Kill by Mr. Grisham, who was a lawyer, so in all his films there is a court scene and the film is so...you're terrified from the word go! You see a child, a little black child, walking along the lane with the shopping in her hand, and you've already seen two men in a car drinking and driving and shouting and you know they will find her—and they do. And they rape her and she is only 10 years old and the father is so upset that he gets into the court room and shoots the two men. And then he's tried. And Mr. Spacey, Kevin Spacey, he is the prosecuting counsel and he is wonderful, with a sarcastic smile that plays about his face all the time. And Mr. McConaughey—he was good. He looks nice and so he only has to present himself, and he could play any number of Gary Cooper parts. I loved the film, I thought it wonderful, and the audience was so engaged that when the verdict was delivered the audience clapped as loudly as the people on the screen.

CL:

One of my favorite quotes of yours is, "A movie star is something you couldn't have invented for yourself if you'd sat up all night." Now that you've been in all these films, do you consider yourself a movie star?

QC:

Well I wouldn't say I was a movie star, I think you have to be in a major movie project before you can be considered a movie star. But almost all of the movie stars were what Mr. O'Connor calls "Auto Facts"—they were self-invented. If you told the movie industry that you could invent a woman for them who was hardly visible to the naked eye, that half her height was the lifts on her shoes, and the other half was the fruit in her hat and between she wore stockings made of fishnet so wide that whole haddocks could have escaped, they would have said, "No, we don't want such a woman—what would we do with her?" But she was Carmen Miranda and she became the highest-paid movie star in the world! That's wonderful!

CL:

Are there any actors today that you feel fit into that definition?

QC: Not really. The great exaggeration has gone out, which is a pity because it made it such fun. [Like] Mae West, who made fun of everything, including herself. In Klondike Annie, Miss West plays the mistress of a Chinese gentleman in San Francisco, and she murders him and she gets on a boat which is captained by Victor McLaglen, and she sails away to the Klondike. And on the boat is a Salvation Army lass who dies. And Miss West sees her opportunity and puts on the Salvation costume and it is tight from the knees to the nipples and the bonnet can't be tied up because of her hair, which is like boiled snow, and it just rests on top and the ribbons hang down. And she walks through the snow in the Klondike into a hut with a stove and a chimney and she sings to the miners, "It is better...to give...than toreceive." And the whole thing is absolute nonsense! But she carries it off with such conviction that you never lose interest.

CL:

Who today is a glamorous movie star? Who is exaggerated?

There's no exaggeration.

CL:

What about Madonna?

QC:

Madonna is exaggerated, but Madonna is only exaggeration. She can never be a star because she lacks remoteness. They all had that. You see, when I was young the word was feminine, the word Movie Star meant a woman, and the men were in support of them, except for Rudolph Valentino, whose image was feminine—now I don't mean that means he was kinky, that means he projected a capricious, veiled, mysterious, cruel image, and that's what all the women did. They were vamps, the word has disappeared. You see, Garbo offered you a series of calculated frustrations. There's a film in which Raymond Navarro, of all people, reminds Garbo that on the previous evening she lead him to believe that she loved him. And Garbo said, [in Garbo-esque voice] "That...was yesterday." And he did not punch her on the nose. So, "Should we wear our eyebrows thin?" or "Should we wear our eyelashes thicker?"—every woman in England between 1924 and 1931 looked like Garbo because they thought it might be possible to rule the world by the skillful use of cosmetics alone. And then in 1931 they all ran home and shaved off their eyebrows and curled up their hair and they all looked like Marlene Dietrich. But you see, women are so available now. They can't be vamps.

CL:

When you say that someone like Madonna lacks a remoteness, do you mean that they're not detached enough from their audience?

QC:

Yes, they're not so far above us. See, you can't look like Madonna because she looks different every week [laughs]. But you could look like Garbo and you could look like Marlene Dietrich. I saw a film called Morocco and halfway through it a woman sitting behind me said, "She's all stuck on herself." And of course it was true! She lived within this image she created.

CL: You once called Metropolis the "most erotic movie ever made." Do you still stand behind that statement about this movie from the 1920s?

QC:

Yes, oh yes, it's wonderful. Not the most suggestive, but the most erotic—because there's an element of cruelty in it.

CL:

What are movies today doing wrong?

QC:

Any film is at least better than real life, and I still believe that. Because of course it's pitched as high as it can go because it's either the most terrible time in somebody's life or the most wonderful time in somebody's life. And I don't like films that are about ordinary people living ordinary lives doing ordinary things. I did like Shirley Valentine, although she was an ordinary woman. What the film taught her was that you can only have the freedom for which you have the talent. And that's what she had to find out—anyone can go to Greece and drink a cocktail on the edge of the Aegean Sea, but she ends up serving egg and chips to bewildered English tourists because that's all she can do! But it was a lovely film.

CL:

Where do you see yourself continuing in movies?

QC:

I'm only in movies because I consent to be in movies. If you want to be in movies, you go into the Lower East Side of Manhattan and you stand still, and someone says, "Would you like to be in our movie?" And if you say yes, then you are taken to a dim cellar decorated in the worst possible taste and you're given a costume to put on and you're given a script, which impresses you, a thick script with plastic binding and beautifully typed—and no one takes any notice of it. And someone comes in and says something to you and you say, "What do I say to that?" and someone says, "What does Quentin say to that? What was the question?" And somehow a film gets made. And I have now found out the secret of them: They are not intended for cinemas, they go into video stores. They are never seen because the video tape is a sealed box. So you've got a sealed thing about that size, you can't get at it, and you're asked forty dollars for it—why should anyone pay forty dollars for something they can't find out anything about? And if everyone in the world had your videotape, you wouldn't become rich. But they all make them. They all want to be movie directors, and I don't know why, because it's a thankless job. No one has ever heard the name of a movie director except for Hitchcock, who had in his contract that he had 100 percent of the main title, that is to say his name was as big as the name of the film. But no one else has ever heard of anybody! And with all that bother and all that stress and people muttering about you and not doing what you say and you're up for weeks, wondering what to do, time going by, money being spent—but they all want to do it.