|

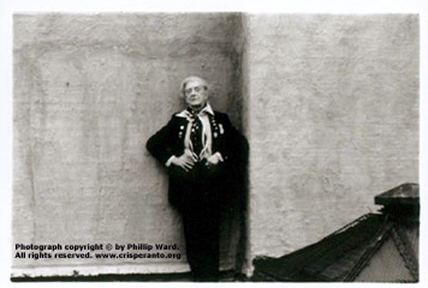

THE ENGLISHMAN IN NEW YORK Chats with Quentin Crisp by Owen Keehnen |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Quentin Crisp was born on Christmas Day in 1908 and lived without compromise right from the very start. In 1930s England he was “not merely a self-confessed homosexual, but a self evident one” with lilac hair, eye shadow, capes, scarves, and blouses. Unable to find a place in proper society Quentin carved his own place—as a male prostitute, a nude model, a window dresser, and an assortment of fringe careers. He first came to public attention in the 1960s with a radio interview and afterward was approached to write his autobiography. With the publication of The Naked Civil Servant and the subsequent film of the same title starring John Hurt, Mr. Crisp’s star rose to even greater prominence and an extremely unique celebrity was born.

At the ripe age of 72, when most are ready to settle back into their comfortable life niche, Quentin Crisp moved to New York City at the invitation of Michael "A Chorus Line" Bennett. In 1981 he became a resident alien and vowed never to leave. In the years following he wrote How To Have A Life-Style, Hot To Go To The Movies, and The Wit and Wisdom of Quentin Crisp. He appeared in such films as The Bride, Resident Alien, Homo Heights, and most notably as Queen Elizabeth I in Orlando. He appeared on stage both as an actor (The Importance of Being Earnest) and lecturer (An Evening with Quentin Crisp). He was in a Sting video, was the film critic for Christopher Street magazine, and a diarist in the New York Native. A virtual career flourished around his unique place in the world. Quentin Crisp was also the ultimate interview. He was virtually always at home in his one room apartment in New York. There was no middleman in setting up an interview. He was listed in the New York phone directory and when I wanted to do an interview I just called him up and we talked. He would do that with everyone and anyone. He loved to chat on the telephone and go to movies, and he was always willing to have someone take him to lunch. Those were his favorite pastimes. Sadly, Mr. Crisp passed away on November 21, 1999 at the age of 90 . . . but, oh, what a ride it had been! What follows is a conglomeration of three formal interviews conducted with Mr. Crisp following his 82nd, 87th, and 88th birthdays. OWEN KEEHNEN: Happy birthday. QUENTIN CRISP: Why thank you, that’s very kind of you. OK: Were you at all charmed by being born on Christmas? QC: I don’t think so. I was very ill immediately after I was born. I had pneumonia and was wrapped in cotton wool, an ambience from which I keenly felt my exile. OK: So other than that how was it being born a Christmas baby? QC: I don’t know, I don’t remember. I was very much embarrassed by Christmas when I was young. OK: Why? QC: My mother gave me half a crown to buy something for my father and my father gave me half a crown to buy something for my mother and they both thanked me. Who did they think they were kidding? OK: Your number is listed in the Manhattan phone directory and people call you at all hours, mostly with questions, what kind of things do they usually want to know? QC: Sometimes they want to know about England. Would it be easy to live there, what would it be like? They know the weather is bad, but they don’t know much else. Sometimes they have problems and want to come to New York and they’ll ring me up from far away and ask me if I know anywhere they might live. Perhaps they don’t realize I live in one small room and could never put them up. Sometimes they ask very different things. A woman phoned me a little bit ago and wanted to know how to prevent her lipstick from failing. OK: What did you tell her? QC: I said never eat anything, never drink anything, never kiss anything. OK: How are you doing? QC: I’m all right. I’ve lost the use of my left hand so I can’t type anything anymore. Also, New York Native, the kinkiest paper in the world that used to publish my diary, has folded. So my career as a writer has ended. OK: Did you make any New Year’s resolutions? QC: I read somewhere that St. Teresa said we should treat all people as though they were at least better than ourselves and I thought that was so wonderful that I resolved to do it. OK: Describe a typical day in the life of Quentin Crisp. QC: I like to spend either one or two days a week without ever leaving my room because that’s the only way you recharge your batteries because once you are out of doors in New York you’re in the smiling and nodding racket. Everyone who’s been on television once or twice or more in New York wears an expression in public of fatuous affability because you may be photographed at any moment. OK: What are your living circumstances? QC: I live in New York as I did in England, in a rooming house. OK: What are the advantages to that? QC: I have never found out what people do with the rooms they’re not in so I have always lived in one room. Here my room is smaller, colder, and three times as expensive. If anything is wrong with New York it’s that the summers are too short, the winters are too cold, and the rents too high. OK: If you were to create a Quentin Crisp room what would it look like? QC: I would furnish it with only what is absolutely necessary—a bed, a chair, a stove, and a refrigerator. That is all that is in my room. There is nothing that is unnecessary, nothing that is a decoration. There are no pictures on the walls, no knickknacks balanced on things. I find that all a waste of time. OK: You also have a reputation for taking notoriously long baths, is that where you do most of your thinking? QC: Well, I no longer take those baths for two reasons. One, I have eczema and it has been suggested that having a bath is a bad idea. Secondly, the bathroom in this house is on the floor above me and the lavatory is in the bathroom so you could never stay in the bath for long fearing you would keep people away from the lavatory. The shower is on the floor I live on. I only take showers now. OK: You’ve become quite a film star recently. You were wonderful in Orlando. QC: Everyone likes Orlando. Of course, it was a film I never would have seen in a thousand years if I hadn’t been in it. OK: What was it like to portray Elizabeth I? QC: Hell, absolute hell. The costume was very heavy and had to be dragged across the lawns of Hatfield House. I wore two rolls of fabric about my waist to make a sort of bustle, and then a hoop skirt tied around my waist and then a quilted petticoat and then an ordinary petticoat and then a dress. OK: You previously remarked that you never do drag because it makes you appear more masculine. Did that film experience change your mind? QC: No. I wore very elaborate drag in the film and was made-up and had a wig and all that. I couldn’t go to that much trouble in real life. OK: And you were in one with Holly Woodlawn last year too . . . QC: Resident Alien. It has no plot. It shows me wandering about, talking to a lot of people, and having a great meal. People are asked their opinion of me which they give… OK: How was filming Homo Heights with Lea DeLaria? QC: That was very frightening. OK: How so? QC: I never understood what I was doing. The producer said the line I was to say for me and then I said it myself and then we proceeded to the next line. OK: How was Ms. DeLaria? QC: She was quite nice, very good. OK: So did you ever imagine or fantasize yourself as a film star? QC: No, I used to learn to imitate all the female film stars, but I never imagined I would be one. OK: Whom did you used to imitate? QC: Well, you know, all homosexuals have a capacity for imitating other people and we learned all their voices in certain cafes and spoke like Garbo or Dietrich or whomever. The easiest people to imitate were Mae West and Bette Davis. Everyone imitated Bette Davis. OK: And now with Orlando you have both played Queen Elizabeth I too? QC: I didn’t act at all. I was just myself in all those terrible clothes. I could never even leave the trailer without someone lifting a whole lot and saying, “Now put your foot down, now the other foot down . . . ” OK: You’ve also played Lady Bracknell on stage in The Importance of Being Earnest. What do you think is the most difficult thing about acting? QC: I don’t really act. For instance, when I played Lady Bracknell I never thought, “What would it be like to be a middle-aged woman in Victorian England faced with getting her daughter safely married.” I just went on and said the lines. OK: John Hurt portrayed you in the biographical film The NakedCivil Servant. How was your life changed for the screen? QC: I really don’t think it was changed. I think it was more or less like the book. I was surprised how like the book it was. Very accurate. I thought it was wonderful. However, when you cram 60 some years of someone’s life into an hour and a half, with commercials for dog food, which makes it an hour and twenty minutes actually, it seems as though not a day went by without something terrible happening when in fact days, perhaps weeks, perhaps even months went by with nothing happening at all. The book is sadder and more rambling than the television play. OK: Is it stranger to see your life portrayed as a subject of a film or to actually see yourself in a role in a film? QC: Both are outrageous. OK: How do you think the American character differs from the British? QC: It’s almost the opposite. Whatever you propose to do in America, everyone is for it. If you say to a group of Americans that you’re getting together a cabaret act they would all say, “what are you going to wear? What are you going to do?” If you told English people that you were getting up a cabaret act someone would say, “For God’s sake, don’t make a fool of yourself.” Americans tend to be forward looking and optimistic. OK: Living in England and then coming here. What are your feelings about Princess Diana being so frequently in the press? QC: I think the reason is simple. Princess Diana is the first person ever to enter Buckingham Palace who was good looking. Americans are obsessed with physical beauty. In England beautiful women are under suspicion. OK: Do you have a definition or measure for beauty? QC: I don’t think there is one. In the movies beauty is not a woman but a man’s idea of a woman. What made Marlene Dietrich great was what Mr. Von Sternberg thought of her. What made Garbo great was what Mr. Stiller thought of her. All they had to do was to be able to portray that. OK: How do you rank beauty, fame, wealth, and love? QC: I would say beauty is the best of those because it can be made to produce the other three. I don’t think I understand what love is really. OK: Have you ever been in love? QC: Never. I don’t know what it means. OK: Going back to the royals. What do you think about all the Princess Di and Fergie brouhaha (scandals, marriage problems)? QC: I think it’s an awful pity that the day has come when valets write books about their employers and things like that. I think it’s bad. But of course, it may be partly that the people concerned aren’t sufficiently guarded. OK: Do you think it’s a symbol of the decline of romanticism? QC: I think romanticism in the sense of someone to adore unconditionally has been going out of style for a long time. In America it was the movie stars . . . but now there are no movie stars. In England, it’s the royal family. People have become envious and embittered. OK: What changed? QC: The distance between the star and the stargazer got less. When the distance was infinite nobody ever expected to be anything like the great stars or royal personages. But now everybody is much nearer, everybody has a greater chance of being famous or notorious in some way. At one time they were too far away and people never thought, “What has she got that I haven’t got?” But now they do. OK: Have you ever reviewed one of your own films? QC: I reviewed The Bride, but I don’t believe I said whether I’d been good or bad. OK: Was it strange to see yourself on the screen? QC: I suppose it would have been stranger if I’d never seen myself on television. You’re always horrified. In your dreams you imagine you have a great deep rich voice and then you find you have this rather high flat squeezed out voice. You think you have beautiful big dramatic gestures and you find of course that it is often fiddling. OK: You met Sting during the filming of The Bride and he wrote the song "An Englishman in New York" about you. What exactly clicked between you two? QC: I don’t really know. He came to America and telephoned me and took me out to lunch and told me he was going to write songs about exiles. We had a long conversation about it. He never said he was going to write about me specifically. Much later I was told the song had been written. I don’t know why really, perhaps I captured his imagination for a while. OK: You’re even in the video? QC: Yes, I walked up and down West Broadway and everyone who’s seen the video says, “You were so cold.” It was done in February and I was walking up and down the street holding my hat, holding onto my scarf in this howling gale, lurching up and down the street because I have terrible rheumatism—but we got it done in the end. Mr. Sting is very gentlemanly, very courteous. OK: When you came to the United States it was by invitation of Michael Bennett. QC: Yes, that was very nice. He paid my fare, my agent’s fare, and put us up in The Drake Hotel. My first night here he took me to Sardi’s. I’d seen it in the movies, but never in a restaurant had I seen such waving, screeching, kissing, and rushing from table to table. If it happened in England the proprietor would put a stop to it, and if he didn’t the staff would leave. OK: And how do you think living in America all these years has changed you? QC: It’s changed me in that I am no longer afraid of the world. I’m no longer hostile to the world; my image is no longer self-protecting because in America everybody is your friend. In England nobody is your friend. Nobody ever speaks to you in public. OK: Why is that? QC: I think the English treasure their indignation. OK: You were wearing make-up in the streets of London in 1931. What led to that sort of self-assertion? QC: It happened gradually. Nowadays people say when did you come out, but I never came out because I was never in. I was a hopeless case from the day I was born. I don’t ever remember not being laughed at by my brothers or my sisters or my parents as a child, or by the other boys at school as you can well imagine, or by the people I worked with when I went out in the world. I suppose it was a gradual process of deciding how I wanted to present myself. In effect my disease became my destiny. OK: Do you consider being gay a disease? QC: Well, it certainly is something peculiar. People always say it’s perfectly normal - well it isn’t perfectly normal. Very few people are gay and most people are ordinary so you have to regard yourself as unique. You have to live through it and not go on apologizing for yourself. OK: Going back to your childhood, did having everyone laugh at you hurt you a lot? QC: I hated it in the beginning, but eventually you get used to it. As Philip O’Connor says in his wonderful book, The Memoirs of a Public Baby, “The day comes for everybody when you have to do deliberately what you used to do by mistake.” Once you learn to do this, then the jokes become your jokes. OK: Did you have any role models growing up? QC: I think role models are a new idea. I don’t ever remember thinking, “That is what I’d like to be like.” OK: Who is someone you admire today? QC: Elizabeth Taylor. She’s so rich, so beautiful, so plucky, and so funny. OK: What celebrity have you been the most nervous to meet? QC: I don’t know if I’ve ever met any. Someone offered me the chance of writing up Ms. Minnelli, but I was frightened and didn’t take it on and go meet her. Ms. Minnelli is very bold and I’m very timid. I just didn’t think it would have worked. I would be frightened by most celebrities I suppose. OK: Do you think homosexuals still view masculinity as sacred and still believe that the “obviously gay” are spoiling it for everyone else. QC: Oh yes. I think they resent the effeminate. I don’t know quite why. Originally I think everyone thought all homosexual men were effeminate because those were the only ones they could see. I think straight-acting gay men resent the fact that there are still those around who keep up the image of homosexual men as effeminate. OK: So you see it as sexist? QC: Yes. There’s no sin like being a woman. When a man dresses as a woman everyone laughs, when a woman dresses as a man nobody laughs. When Marlene Dietrich appeared as a petty officer in Seven Sinners nobody laughed, they thought she looked wonderful, and she did. Being a man is seen as uplifting yourself and being a woman is seen as degrading yourself. OK: Do you think that is changing at all? QC: Not really. When I saw the Japanese film The Black Lizard and the people realized the cabaret singer was really a man they laughed, even in a screening where nobody ever displays any emotion, nobody ever laughs or screams or cries. OK: Going back to wearing makeup in the streets of London in 1931, was the harassment considerable? QC: Oh yes. The only thing the movie, The Naked Civil Servant, doesn’t show is the crowds that followed me in the street, so much so that traffic was stopped. OK: And yet you never attempted to alter your behavior? QC: I wasn’t tempted because I was stuck with it. Even if I hadn’t worn make-up and dyed my hair I could never have disguised my effeminacy. That was obvious to everyone. Of course I lived in a room by myself and didn’t have to accommodate anyone or else it would have been awkward. They would have said, “Must you go out looking like that?” and then there would have been a row. But since I was only accountable to myself it was easier. OK: What do you think of the current "queer" movement? QC: Well, I don’t think you can really be proud of being gay because it isn’t something you’ve done. You can only be proud of not being ashamed. I’m glad that they’re no longer ashamed and that they don’t find their lives difficult to live. But of course, if they take this protest very far it inevitably does produce an adverse reaction in the rest of the world. OK: Such as . . . QC: If you rush in and out of cathedrals while religious services are going on you do not make the public more ready to accept you. OK: Do you think the gay community is becoming more or less assimilationist? QC: I think it’s becoming less. If we crept forward we would arrive at the heart of civilization, but if we charge forward them there will be resistance. As far as I can tell we want to be separate but equal. OK: In your opinion what is the most shocking thing going on in the world today? QC: I suppose I’m shocked by all this business about abortion. You see people lying like porpoises in the entrances of family planning clinics and on the same program you hear that a garbage man has found a baby four hours old in a paper bag in the alleyway. Seriously, doesn’t that tell you that there must be abortion? OK: Any message to gay and lesbian youth? QC: Tell them they don’t have to win. Everyone has a parent who says, “Did you come in first” and if you haven’t you’ve lost face somehow. It’s a terrible pity that people do that. “Did you score goals? Did you score more goals than other people?” It’s terrible, you don’t have to win—you just have to play. OK: How similar are you to your public persona? QC: I think I’m no different. I try to make my image and myself one because if you adopt an image you snatch out of the air it never really works. You have to build your public image on what you are and then you can’t go wrong. I try not to allow there to be one. Of course, I am more dolled up and ready for the world when I’m in the world. I can’t imagine if someone could look through the he window of this room that they would see me doing something that would make them say, “Oh I never dreamed he’d do anything like that!” OK: You’ve been quoted as saying your life has been a matter of chance…does that remain true even today? QC: I try to do everything people ask of me. I try not to be slipshod in my relations to people and the world. I try to answer letters and keep appointments, so in that sense my life isn’t a matter of chance. And also, my coming to America was not a matter of chance, in fact when I told me agent in England that I wanted to become an American he said in a tired voice, “As it is the only preference you’ve ever expressed, we should try and do something about it.” OK: Do you consider yourself an artist or a work of art? QC: Well, I’m not an artist at all. I don’t know if I’m a work of art or if so a rather broken down one. I have been called an “auto-fact,” meaning a self-created being. I suppose I am in that I’ve taken troubles with my, what nowadays would be called, “image.”  OK: Did you ever imagine that you would become famous? OK: Did you ever imagine that you would become famous?QC: No, I never imagined it. I don’t know how it’s happened—I just cling on. My agent says, “You can’t just do fame,” but you can. OK: How is that? QC: Never refuse to answer questions, never refuse to be photographed, and never flinch at the flashes. I shouldn’t be surprised if in the next 25 years universities will offer a degree in fame. Owen Keehnen has worked as a journalist, book reviewer, and interviewer for a number of years. Currently, the Chicago-based author is completing a trilogy of interview books on gay XXX stars, finishing a horror novel, and supporting himself as a massage therapist. He is also launching a Web site, racksandrazors, which celebrates independent horror films.

|

||