AN INTERVIEW WITH

QUENTIN CRISP

by Linda Eisenstein

"In England there is no happiness," says the venerable British writer, now a blissful Manhattanite. "Here, happiness rains down from the skies." Then he sighs into the phone, a rueful catch to his voice. "Americans," he says sadly, "want luxury more than they want happiness."

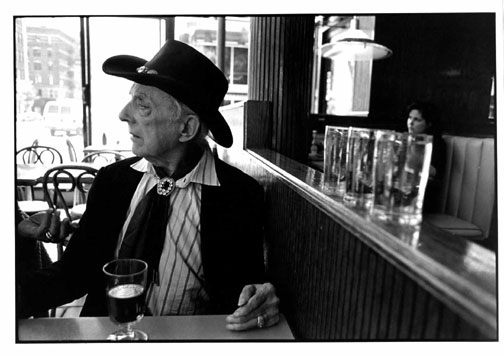

At 90, regal and mischievous as ever, Quentin Crisp is a legend — not just for his writing, but for his very way of being. He's a delightful conversationalist: epigrams bubble from him like vintage champagne. After an hour's chat, you'll find a giddy smile wreathing your face.

Cleveland audiences can finally share the bounties of his personality. With his first area appearance, he brings his dry wit and wisdom to Cleveland Public Theatre Thursday. In An Evening with Quentin Crisp, he will hold court for three days — extemporizing for an hour, then answering audience questions.

Crisp has been charming audiences with his gently outrageous opinions in this informal setting since the late 1960's, when his agent first booked him in a London pub.

At first glance, Crisp might seem an unusual philosopher of happiness and success. His remarkable 1968 memoir The Naked Civil Servant is the story of a singular personality forged in the crucible of public revulsion and scorn. An effeminate homosexual born in 1908 who hennaed his hair and wore makeup as far back as the 1920's, he lived by the philosophy "Don't keep up with the Joneses: it's easier to drag them down to your level." The result was a black-comic litany of worldly failure, bouncing from job to job until he began to model in London art schools.

At the age of 72, after the publication of his critically acclaimed autobiography, he moved to New York's East Village, and his happy American life began. The author of tongue-in-cheek works like How to Have a Lifestyle, How to Become a Virgin, and Manners from Heaven, he has lived to see his memoir made into a 1978 television film with John Hurt ("my representative on Earth").

Crisp himself has been in a number of films — from the Frankenstein remake The Bride with Sting, to the party scene in Philadelphia, to a regal appearance as Queen Elizabeth I in Sally Potter's Orlando — "a lovely film, but unabashed festival material that can never be shown to real people."

He considers his late movie career a natural extension of his life as a recognizable New Yorker. "If you don't want to be in a movie, you have to keep moving," he says. "The moment you stand still in Manhattan, someone will sidle over, saying 'Will you be in my film?'"

As someone who never likes to say no, he was recently the subject of a documentary about his American years, Resident Alien. "That took up more time, much more concentration," he admits. Crisp has lived in austere simplicity for eighteen years in one room of a rooming house on the Lower East Side, on a block with Hell's Angels, which made filming a challenge. "You know film: equipment and cables everywhere. Things were always getting moved or broken."

Beyond his writings and film appearances, Crisp's most polished work of art is his own burnished self. Yet despite living in downtown Manhattan, where you can't throw a stone without hitting a performance artist, he's not particularly a connoisseur of solo performance. "I haven't really seen any," he admits, "except Miss Penny Arcade, tearing off her clothes and haranguing the audience. She is quite something." You can hear the smile in his voice.

His own tastes run more to the talents of actress Ruth Draper, performing a sketch called "The Italian Lesson" on a bare stage. "There she was, a middle-aged woman in a party dress, playing a rich American woman struggling with the first sentence of The Divine Comedy, while interrupted by her children, the maid, the nanny, the dog," he recalls. "Oh, she was phenomenal."

It's a telling recollection. Crisp too seems a representative of a different time and place: a land of gentility, grace, and quiet wit, partly of his own invention. He is indeed a Resident Alien, sailing serenely through a culture that elevates the rude and crude. When asked about manners, he says "I've now discovered Saint Theresa: we must treat all people as though they were at least better than ourselves. It altered her whole life. People want to be the equal of others; 'I'm as good as they are.' A great pity. One must accept defeat."

As both his wit and longevity have turned him into an elder statesman in the gay community, Crisp's controversial comments about homosexual identity have sometimes gotten him in trouble with gay activists. "Gay people? They are very different, but it's gone to gay people's heads." He quotes a line from Harvey Feirstein's Torch Song Trilogy: "If it's so natural, if it's so part of everyday life, why do we never talk of everything else?"

His unique style and propensity for epigram have made him frequently compared to Oscar Wilde, whose example Crisp finds pitiful. "His style," Crisp has written, "was never a part of him but rather a sequined Band-Aid covering a suppurating sore of self-hate." In Crisp's philosophy, it takes both personal style and self-acceptance to create happiness, the centerpiece of his program for successful living.

"And no housework," he adds impishly. "A woman friend once shouted at me: 'No wonder you're so nice to everybody, you don't do any housework.' Women who clean are in a blind rage by half past ten in the morning."

Read Ms. Eisenstein's review of An Evening with Quentin Crisp

when he performed his one-man show at Cleveland Public Theatre

on September 17, 18, 19, 1998.

Linda Eisenstein's award-winning plays and musicals have been produced throughout the U.S., and in England, Canada, Australia, South Africa, and the Philippines. Her plays have been published by Dramatic Publishing, and are available in collections by Penguin, Heinemann, Vintage, and Smith & Kraus. Her poetry and fiction have appeared in journals such as Kalliope, Kinesis, Amelia, and Blithe House Quarterly.

The author of Practical Playwriting — a book of essays on the craft and business of writing for the stage — she has taught scriptwriting at Denison University, Cleveland State University, E-script, and many writers' conferences. A theatre journalist and reviewer, she is the theatre columnist for angle: a journal of arts + culture and Cool Cleveland and a frequent contributor to the Cleveland Plain Dealer.

A resident writer in The Playwrights Unit at the Cleveland Play House, she is a member of the Dramatists Guild of America, Inc., ASCAP, the International Centre for Women Playwrights, and the Literary Managers & Dramaturgs of the Americas. Born in Chicago, raised in San Francisco, she makes her home in Cleveland, Ohio.

This interview was originally published in the Plain Dealer, September 1998.

The author of Practical Playwriting — a book of essays on the craft and business of writing for the stage — she has taught scriptwriting at Denison University, Cleveland State University, E-script, and many writers' conferences. A theatre journalist and reviewer, she is the theatre columnist for angle: a journal of arts + culture and Cool Cleveland and a frequent contributor to the Cleveland Plain Dealer.

A resident writer in The Playwrights Unit at the Cleveland Play House, she is a member of the Dramatists Guild of America, Inc., ASCAP, the International Centre for Women Playwrights, and the Literary Managers & Dramaturgs of the Americas. Born in Chicago, raised in San Francisco, she makes her home in Cleveland, Ohio.

This interview was originally published in the Plain Dealer, September 1998.